There is consternation at Wikipedia over the discovery that hundreds of novelists who happen to be female were being systematically removed from the category “American novelists” and assigned to the category “American women novelists.” Amanda Filipacchi, whom I will call an American novelist despite her having been born in Paris, set off a furor with an opinion piece on the New York Times website last week. Browsing on Wikipedia, she had suddenly noticed that women were vanishing from “American novelists”—starting, it seemed, in alphabetical order. In the A’s and the B’s, the list was now almost exclusively male:

I did more investigating and found other familiar names that had been switched from the ‘American Novelists’ to the ‘American Women Novelists’ category: Harriet Beecher Stowe, Ayn Rand, Ann Beattie, Djuna Barnes, Emily Barton, Jennifer Belle, Aimee Bender, Amy Bloom, Judy Blume, Alice Adams, Louisa May Alcott, V. C. Andrews, Mary Higgins Clark—and, upsetting to me: myself.

The word that came to mind—and the Times used it for the headline—was sexism.

And who could disagree? Joyce Carol Oates expressed her view on Twitter: “Wikipedia bias an accurate reflection of universal bias.  All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.” Elaine Showalter tweeted in response that this was not what she’d had in mind in titling a book A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers: “Wikipedia is cutting down on American writers category by taking women out of it! A new step backwards.”

All (male) writers are writers; a (woman) writer is a woman writer.” Elaine Showalter tweeted in response that this was not what she’d had in mind in titling a book A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers: “Wikipedia is cutting down on American writers category by taking women out of it! A new step backwards.”

At Wikipedia, all hell broke loose.

(Let’s pause here to flag the phrase, “at Wikipedia.” Wikipedia is a notional place only. It is not situated in a sleek California corporate campus, like Google in Mountain View or Apple in Cupertino, but instead distributed across cyberspace.)

This kind of thing is usually bruited and argued on Wikipedia’s “Talk” pages. After the Filipacchi article, Jimmy Wales, Wikipedia’s cofounder, created a new entry on his personal Talk page under the bold-face heading, “WTF?” Wales does not give orders or directly cause things to happen. He is more of a

noninterventionist god. He is often referred to simply as Founder (capital F) or Jimbo. Anyway, he wrote:

My first instinct is that surely these stories are wrong in some important way. Can someone update me on where I can read the community conversation about this? Did it happen? How did it happen?

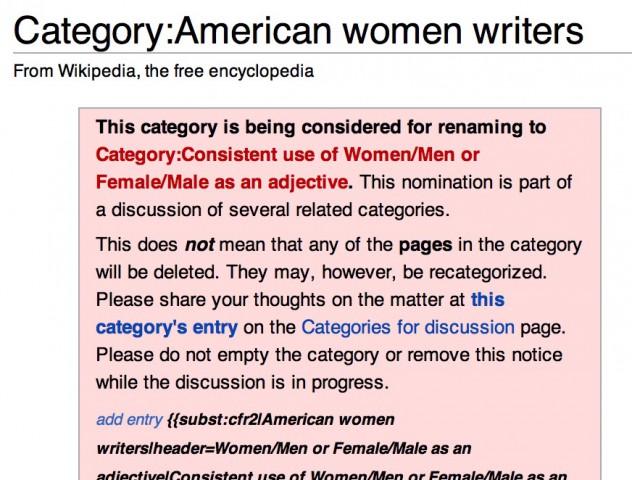

Heated argument broke out on a page set aside for discussion of changes to Wikipedia categories. Categories are a big deal. They are an important way to group articles; some people use them to navigate or browse.

Categories provide structure for a web of knowledge—not a tree, because a category can have multiple parents, as well as multiple children. Wikipedia lists 4,325 Container categories, from “Accordionists by nationality” to “Zoos in the United States.” There are Disambiguation categories, Eponymous categories—named for example, after railway lines like Norway’s Flåm Line, or after robots (there are two: Optimus Prime and R2-D2)—and at least 11,000 Hidden categories, meant for administration and therefore invisible to readers. A typical hidden category is “Wikipedia:Categories for discussion,” containing thousands of pages of logged discussions about the suitabilities of various categories. Meta enough for you? Some categories under discussion now are Avenues, Omniscience, and “Equestrian commanders of vexillationes.”

It’s fair to say that Wikipedia has spent far more time considering the philosophical ramifications of categorization than Aristotle and Kant ever did.

On Wednesday a formal proposal appeared for discussion: “Propose merging Category:American women novelists to Category:American novelists.” Nominator’s rationale: “As per gender neutrality guidelines, gender-specific categories are not appropriate where gender is not specifically related to the topic. This subcategory also creates the unfortunate side effect that Category:American novelists contains only male novelists.” Many users quickly posted comments agreeing. One user “struck out” two of these votes, on the ground that they appeared to have been submitted by “sock puppets”—new identities created by an existing user for purposes of deception—or at least by people who had created new Wikipedia accounts specifically for the purpose. Yet another user objected to the striking out of the votes:

These are people who have bothered to get involved. By pushing them out of this conversation, you are contributing to the continuing inability for newcomers to feel comfortable here. Especially women. Which is of course, the subject of the article being discussed.

Which, of course, it was. Wikipedia is periodically accused of being a boys’ club. “Around 90 percent of Wikipedia editors are men, and it shows,” New Scientist said earlier this month. Many Wikipedians agree and would like to do something about it. A large majority of commenters voted “Merge.” Some deployed the terms “ghettoization” and “back of the bus.” Then again, a few are voting for ghettoization—or as they say, “Diffuse women but not men,”diffuse being the term for sending members of a parent category out into a subcategory. At least it’s arguable that “women novelists” is a category of cultural and sociological interest. It was noted that Wikipedia features an extensive article on Women’s Writing in English, as part of Wikiproject Gender Studies and Wikiproject Women’s History.

“We should not let the media impose their view of political correctness on Wikipedia,” wrote Petri Krohn, who identifies himself as a Finnish “writer and Internet commentator.” He added—I think with a straight face—“We might also add some generic warning on American people category pages that they mainly contain white males and one should look into the subcategories.”

To ask Jimbo’s question: how did this happen? It turns out that a single editor brought on the crisis: a thirty-two-year-old named John Pack Lambert living in the Detroit suburbs. He’s a seven-year veteran of Wikipedia and something of an obsessive when it comes to categories. He creates a lot of them. Last year he briefly created Category:American people of African-American descent. Then he raised hackles by recreating the defunct category American “actresses,” a word that others felt belongs in the same dustbin as “poetess.”

On April 1 Lambert started working alphabetically through all American novelists and moving the women into Category:American women novelists instead. First he did Patricia Aakhus, at 5:44 PM. Two minutes later, Hailey Abbott. Then Megan Abbott—pausing also to add her to Category:University of Michigan alumni. Then Diana Abu-Jaber, Alice Adams, Lorraine Adams, Renata Adler…. He did English women novelists, too; also Australian, German, and Moroccan. At 8:51, he created a new category, Nigerian women novelists, and put Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie there.

By the end of the day he’d gotten to the D’s: so Daphne du Maurier is now an English woman novelist. Like most people, she falls into multiple categories; she is also a “bisexual writer,” a “British historical novelist,” a “Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire,” an “English person of French descent,” an “English short story writer,” a “writer from London,” and an “LGBT writer from England.” But not (as of this morning) an English novelist.

And so it went. The next day Lambert was briefly sidetracked by a discussion of whether there should be a Category:Jeans enthusiasts (for “celebrities and famous people who are always wearing or frequently spotted wearing jeans”), but then he got back to work and A. L. Kennedy, till then a Scottish novelist, became a Scottish woman novelist. On April 3 he created a category for Greek women screenwriters; so far it has only one member.

The debate that broke out when Filipacchi’s opinion piece appeared is still running, and the issue appears to be more general and pervasive than most had originally thought. Throughout Wikipedia, in all kinds of categories, women and people of nonwhite ethnicities are assigned only to their subcategories. Maya Angelou is in African-American writers, African-American women poets, and American women poets, but not American poets or American writers. Many editors are saying that people need to be “bubbled up” to their parent categories.

Lambert vehemently disputes suggestions that he is motivated by sexism (or racism, as the case may be). He cites principles of Wikipedia categorization: arguing, for example, that huge categories should be broken up and “diffused” because they become useless for navigation. “This whole hullabaloo is really missing the point,” he told me. “The people who are making a big deal about this are not being up-front about what happens if we do not diffuse categories.” Others argued that laypeople are simply misunderstanding the purpose of a big category like American novelists. “It is really a holding ground for people who have yet to be categorized into a more specific sub-cat,” said a user called Obi-Wan Kenobi. “It’s not some sort of club that you have to be a part of.”

The editor who originally created the American women novelists category—a Londoner named Gareth E. Kegg—voted to merge it with American novelists and said that he had hoped the category would be “an inspiration to young women to know how many others have written before.” He was appalled, he said, “that there are less Wikipedia articles on women poets than pornographic actresses, a depressing statistic.”

A user called lmurchie created a new category: American men novelists. Immediately other Wikipedians objected. A distinctive feature of the Wikipedia culture is the development of shorthand for various rhetorical devices. For example, an editor has only to say, “A new user created this unhelpful WP:POINTy category, compounding our problems,” and everyone knows that WP:POINT is a link to a page describing a behavioral guideline, titled “Wikipedia:Do not disrupt Wikipedia to illustrate a point.” When one editor argues that it’s unfair to address discrimination only for the American category, another can retort, “Objection: This is the Slippery Slope Fallacy,” with the relevant hyperlink embedded. It’s all very efficient. You can write (and someone did), “It looks sexist, it sounds sexist WP:QUACK.”

For some reason the first two members of Category:American men novelistswere Orson Scott Card and P. D. Cacek, who was also categorized in “American science fiction writers” and “American horror writers.” It took about fifteen hours for someone to realize that Cacek, whose full name is Patricia Diana Joy Anne Cacek, didn’t belong. As of this writing, she is back to being an American novelist and an American woman novelist. Ernest Hemingway is now officially an American man novelist—manly indeed. F. Scott Fitzgerald will be relieved to know that he, too, made the cut.

By the end of the week, swimming against the tide, John Pack Lambert was still removing names from American novelists and adding them not just to American women novelists but to Category:African-American novelists, Category:American historical novelists, Category:American surrealist novelists, Category:19th-century American novelists, Category:American Chicano novelists, some of which he’s creating as he goes. This morning, American Chicano novelists contains only one page, Oscar Zeta Acosta. Acosta also belongs to Hispanic and Latino American novelists, American writers of Mexican descent, American politicians of Mexican descent, Writers from California, People from Modesto, California, and People from El Paso, Texas.

People of Wikipedia! You have a problem.

And Amanda Filipacchi? It seems some Wikipedians need to check the policy on shooting the messenger. The article about Filipacchi is undergoing a flurry of editing, not all well-intentioned. Her categories keep changing. Lambert created a new category, American humor novelists, just so he could move her into it.

~