Kids used to ask each other: If a tree falls in a forest and no one hears, does it make a sound? Now there’s a microphone in every tree and a loudspeaker on every branch, not to mention the video cameras, and we’ve entered the condition that David Foster Wallace called Total Noise: “the tsunami of available fact, context, and perspective.”

When terrible things happen, people naturally reach out for information, which used to mean turning on the television. The rewards (and I use the word in its Pavlovian sense) can be visceral and immediate, if you want to see more bombs explode or towers fall, and plenty of us do. But others are learning not to do that.

The Boston bombings, shootings, car chase, and manhunt found the ecosystem of information in a strange and unstable state: Twitter on the rise, cable TV in disarray, Internet vigilantes bleeding into the FBI’s staggeringly complex (and triumphant) crash program of forensic video analysis. If there ever was a dividing line between cyberspace and what we used to call the “real world,” it vanished last week.

Microblogging and social media intruded sharply upon the chain of events. The @CambridgePolice, having tweeted SUSPICIOUS PACKAGE reports through Thursday night and Friday morning, stopped tweeting in case the 19-year-old fugitive Dzhokhar Tsarnaev was glued to his cell phone like everyone else (“monitoring police response via social media”). And why wouldn’t he be? The internet revealed his supposed Twitter name, which instantly acquired tens of thousands of new followers.

Reddit users assembled a crowd-sourced map of the Thursday-night shootings and carjacking. The @Boston_Police begged other tweeters to stop “Broadcasting Tactical Positions of Homes Being Searched.” Someone instantly registered the domain name shouldIlivetweetthescanner.info in order to post a short message: “NO. NO, NO and NO.”

The slain MIT police officer, Sean Collier, was memorialized on an Officer Down Memorial Page. The Chechen president, Ramzan Kadyrov, a.k.a. kadyrov_95, turned to Instagram to announce that, whatever had happened, it was America’s own fault. One of the more popular Twitter hashtags was #surreal. That would have been useful for television news, too, if they had hashtags.

We need to get smarter about the vectors of time and information flow.

I managed to evade the television for several days after the bombing. You can get your cable news secondhand, via Twitter or the blogs, which is a little like using a mirror to avoid gazing upon the Gorgon directly. If you did that Wednesday afternoon, you knew something was going on when William Gibson tweeted some weather: “Fog ’o news pea soup solid in Boston right now.” Followed minutes later by the London journalist Charlie Brooker: “CNN is essentially just footage of reporters in the street staring in bewilderment at their iPhones.”

Fog of News was right. At 1:16 p.m., the reporter John King told the anchor Wolf Blitzer that the police had identified a suspect. “A dark-skinned male,” he said, a bit nervously, “because of the sensitivities some people will take offense even at saying that.” Blitzer said, “We can’t say whether the person spoke with a foreign accent or an American accent or anything like that, that would be premature.”

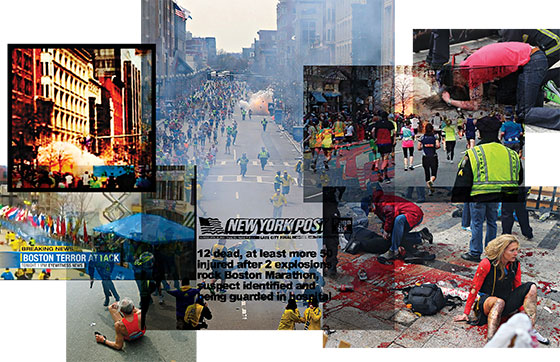

At 1:45, Blitzer cut back to King for “more information, exclusive reporting”—namely, that an arrest had been made. “A dramatic, dramatic shift,” King said. Meanwhile, and all along, background video loops: smoke and blood and people running. Carnage recycled as eye candy.

“I want to be precise, and I want to be sure we have it right,” said Blitzer at 1:51. “It’s important to get this information out there to the American public and important to get this information out there in general, but it’s much more important to make sure that we’re precise and accurate.” King replied: “An arrest has been made. Both Fran [Townsend]’s federal source and my Boston source say an arrest has been made.”

None of this, of course, was true. No arrest had been made. No suspect had even been identified. Nor was it “important to get this information out there in general.” There was no information, and no one needed it.

But when everyone is monitoring everyone else, no one can bear to be left out. Fox News, along with the Associated Press, the Boston Globe, and various local stations, leaped in to report the nonexistent suspect in custody. They all cited unnamed sources and later blamed the sources. The Keystone Koppish retreat lasted about an hour. My favorite bit came on CNN at 2:30, from Fran Townsend, former Homeland Security adviser to George W. Bush and now professional television “contributor”:

“The situation is very fluid … There was a misunderstanding, I mean, that was said to me, not so much that we have misunderstood but that there has been a misunderstanding and lots of cross-communications and understandably, as law enforcement tries to work through this, what they’ve got, who it is, what the purpose of that is, and what the next steps are. So, I myself have had conflicting reports, and I wanted just to be clear with you that they think that’s a result of the chaos and the quickly unfolding law-enforcement situation up in Boston.”

Maybe it’s unfair to set down this kind of pressured utterance in print. But cable news generates verbiage in this hollow mode, minute after minute, hour after hour, when people are forced to speak even though they have nothing to say. It’s inherent in the enterprise. In most of what it does, continuous real-time broadcast news is a failed experiment.

We need to get smarter about the vectors of time and information flow. We know what the hurry is, of course. It is devoutly felt at CNN and Fox News that prestige or viewership or both depend on being the first, even if only by seconds, to announce practically anything. They continue to believe this, even though no one remembers which of them was first to announce erroneously that the Supreme Court had overturned the Affordable Care Act—rushing to botch a fact that had been officially released to the entire infosphere and would soon be universally available to everyone. “We gave our viewers the news as it happened,” Fox said smugly later that day.

It starts to feel as though we’re Pavlov’s dogs—subjects in a vast experiment in psychological conditioning. The craving for information leads to behaviors that are alternately rewarded and punished. If instantaneity is what we want, television cannot compete with cyberspace. Nor does the hive mind wait for officialdom. While the FBI watched and tagged and coded thousands of images from surveillance cameras and cell phones, users on Reddit and 4chan went to work, too, marking up photos with yellow arrows and red circles: “1: ALONE 2: BROWN 3: Black backpack 4: Not watching.”

Virtually everything these sleuths discovered was wrong. Their best customer was the New York Post, which fronted a giant photo of two “Bag Men”—who, of course, turned out to be a high-school kid and his friend, guilty of nothing but brown skin. If the watchword Wednesday was crowd-source, by Thursday it was witchhunt. Total Noise. But when the FBI’s database of 12 million mug shots offered no help, what could the authorities do but enlist the hive mind in the search?

Then, if you were really hooked, you joined the manhunt in cyberspace. Reporters tweeted as they ran. @Boston_Police tweeted warnings and at least one license plate. Cambridge residents tweeted the sound of sirens, the chatter on the police scanner, and photos of bullet holes. Outsiders tweeted their love of crowd-sourcing and their disdain for the old media.

“A dozen officer going into our yard …”

“@msnbc says brothers had bomb, @FoxNews says only a trigger @CNN is clueless…”

“SWAT is out on Laurel St.…”

“Boston Police to Twitter: ‘Stop making up fake Twitter accounts, stop tweeting our scanner, stop telling people where we’re going.’ ”

We’re starting to sense what may happen when everything is seen and everyone is connected. Bits of intelligence amid the din; and new forms of banality. Within hours of his death, the world could examine the videos Tamerlan Tsarnaev watched in his YouTube account and, on his Amazon wish list, some books he wanted.

First published in New York Magazine, April 20, 2013.