[First published in slightly different form in The New York Times, Nov. 6, 2016]

We awaken to yet another disturbance in the chronosphere — our twice-yearly jolt from resetting the clocks, mechanical and biological. Thanks to Daylight Saving Time, we get a dose of jet lag without going anywhere.

Most people would be happy to dispense with this oddity of timekeeping, first imposed in Germany exactly 100 years ago, during the First World War. But we can do better. The time has come to deep-six not just Daylight Saving Time but the whole jury-rigged scheme of time zones that has ruled the world’s clocks for the last century and a half.

The time-zone map is a surrealist hodge-podge—a jigsaw puzzle by Dalí. Logically you might assume there are 24, one for each hour. You would be wrong. There are 39, crossing and overlapping, defying the sun, some offset by 30 minutes or even 45, and fluctuating on the whims of local parliamentarians and satraps. The cacaphony of hours confuses global communication. If your teleconference is scheduled for 10:00 BST, will that be Bangladesh Standard Time, Bougainville Standard Time, or British Summer Time?

Let us all—wherever and whenever—live on what the world’s timekeepers call Universal Time, or UTC (though “Earth time” might be less presumptuous). When it’s noon in Greenwich, England, let it be 12:00 everywhere. No more resetting the clocks. No more wondering what time it is in Peoria or Petropavlovsk. No more befuddled headaches crossing the International Dateline from Tuesday back into Monday.

Our biological clocks can stay with the sun, on local time, as they have from the dawn of history. We can continue to live our days and nights as we like, waking and sleeping with the light and the darkness, or not, according to taste. Only the numerals on our devices will change, and they have always been arbitrary.

Some mental adjustment will be necessary at first. Every place will learn a new relationship with the hours. New York (with its longitudinal companions) will be the place where people breakfast at noon, where the sun reaches its zenith around 4 PM, and where people start dinner close to midnight. (“Midnight” will come to seem a quaint word for the zero hour, in places where the sun still shines, and future folk will puzzle over the term “high noon.”) In Sydney, the sun will set around 7 AM, but the Australians can handle it; after all, their winter comes in June.

The human relationship with time changed dramatically with the arrival of modernity—trains and telegraphs and wristwatches all around—and we can see it changing yet again in our globally networked era. It’s time to synchronize our watches for real.

I’m not the first to propose this seemingly radical notion. The visionary Arthur C. Clarke suggested a single all-Earth time zone when he was pondering the future of global communication as far back as 1976. Two Johns Hopkins University professors, Richard Conn Henry and Steve H. Hanke, an astrophysicist and an economist, have been advocating it for several years. Aviation already uses UTC (they call it “Zulu time”), and so do many computer folk. Scientists know that UTC is maintained to the nanosecond by a global array of atomic clocks. Strange as Earth time might seem at first, the awkwardness would soon pass and the benefits would be immense, Henry and Hanke argue. “The economy—that’s all of us—would receive a permanent ‘harmonization dividend.’”

Perhaps you’re asking why the Greenwich meridian gets to define Earth time. Why should only Britain keep the traditional hours? Yes, it’s unfair, but that ship has sailed. The French don’t like it either. With the whole world on Earth time, the English would get a nostalgia bonus. “The U.K. would turn into a time theme park,” tweets John Powers from the Lake District, “where you could experience 9 o’clock as your grandparents knew it.”

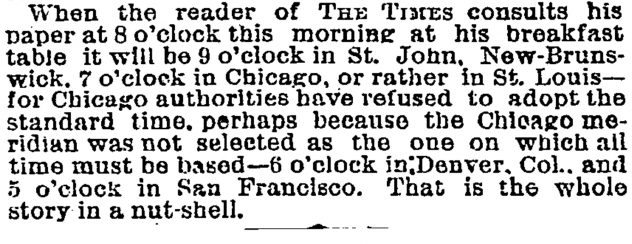

People forget how recent is the development of our whole ungainly apparatus. A century and a half ago, time zones did not exist. They were a consequence of the invention of railroads. At first they were neither popular nor easy to understand. When New York officially reset its clocks to railway time on Sunday, Nov. 18, 1883—known afterwards as “The Day of Two Noons”—this newspaper methodically explained the messy affair:

It was by no means the whole story. Time, that most ancient and mysterious of our masters, seemed to be coming under human jurisdiction. Time seemed malleable. It was no coincidence that H. G. Wells now invented his time machine, nor that Einstein invented relativity soon after. With everything still unsettled, Germany created Sommerzeit, “summer time,” as Daylight Saving Time is still called in Europe. In England, King Edward VII had the clocks on the royal estate moved forward a half-hour—“Sandringham time”—to allow more evening light for hunting.

“There was much talk of relative time, physiological time, subjective time and even compressible time,” wrote the French novelist Marcel Aymé in “The Problem of Summer Time,” a 1943 time-travel story. “It became obvious that the notion of time, as our ancestors had transmitted it down the millennia, was in fact absurd claptrap.”

Aymé was reacting in part to the politicization of time zones: the Nazis imposed Berlin time on Paris when they occupied it in World War II. It is no less political today, no less arbitrary, and no less confusing. Last year North Korea set its clocks back 30 minutes to create an oddball time zone all its own, Pyongyang time—just to show that it could, apparently. On the other hand, China has established a single time zone across its breadth, overlapping six time zones in its northern and southern neighbors.

Drawbacks? Those bar-crawler T-shirts that read “It’s 5 o’clock somewhere” will go obsolete.

It might seem impossible to imagine all the world’s nations uniting behind an official Earth time. We’re a country that can’t get seem to rid of the penny or embrace the meter. Still, the current system is unstable, a Rube Goldberg contraption ready to collapse.

The human relationship with time is changing again. We’re not living in the railroad world anymore. We’re living in a networked world—a zone of experience where the sun neither rises nor sets. What time zone governs Twitter? What time is it on Facebook? There’s plenty to argue about in cyberspace, as in the real world. We could at least agree on the time.